A typology of tipplers

Should you over-indulge (perish the thought) what sort of drunkard might you be? Sanguineous (‘talkative from the beginning’ but ‘perfectly obstreperous’ when fully intoxicated) or perhaps melancholy (initially ‘gloomy’ but then ‘joyousness … breaks in … like sunshine upon darkness)? Into this latter category frequently fell ‘men of genius’ whose minds ‘possess a delicacy of structure which unfit them for the gross atmosphere of human nature. The poet Robert Burns was one such melancholic genius, Samuel Johnson another. Or – should you be a Welshman, a Highland laird or a mountaineer – you might likely fall into the choleric category (‘quick, irritable, and impatient but withal good at heart’)?

These and others were the categories isolated and analysed by the Scottish surgeon Robert MacNish in his very successful Anatomy of Drunkenness, first published in 1827 when he was a twenty-year old applicant to the Faculty of Surgeons in Glasgow.

Forthright in his condemnation of the ‘physical degradation’ that drunkenness had ‘spread over the world’, he was nonetheless both sympathetic to its causes and understanding of its appeal. While some, he thought, were drunkards by choice, the majority were those whom ‘misfortune has overtaken’ or who had been introduced to alcohol by others and found it impossible to regain sobriety. Thus he condemned not only the ‘parental custom of treating children to wine, punch and other intoxicating liquors, but also those ‘female attendants’ who from ‘well-meant but mistaken motives’ introduce nursing mothers to ‘porter [strong beer] and ale’.

The consequences of drunkenness were, he said, ‘dreadful’ and his readers were spared no detail of the sufferings both short- and long-term of over-indulgence. Yet he accepted that the ‘pleasures of getting drunk are certainly ecstatic’ and notes that ‘we drink at first for the serenity which is diffused over the mind’. Indeed he comes across as a man who fully understood the temptations, the pleasures and the consequent pains of alcohol and other intoxicants – including opium, tobacco and the then highly fashionable nitrous oxide (laughing gas).

Different forms of intoxicant produced different effects. Should you be in the habit of taking ‘light wines’ such ‘Champaign, Claret, Chambertin or Volnay’ then your drunkenness might be ‘airy and volatile’ but you would rapidly gain ‘an ominous rotundity of face’, and, not infrequently, corpulence’, the more so if your tipple of choice was fortified wines such as port, sherry or Madeira. Spirit drinkers on other hand tended to the ‘spindle-shanked’ with ‘glazed and hollow eyes’ whilst those who abused ‘malt liquors’ (ie beer, porter, stout etc) become ‘loaded with fat, the eye prominent and the face bloated and stupid’.

This latter form of drunkenness was, reckoned MacNish, ‘peculiarly of British growth’ and was most to be found in ‘innkeepers and their wives, recruiting sergeants and guards of stage-coaches’. Taken to extremes it was inevitably fatal with death coming ‘by some instantaneous apoplexy or rapid inflammation’.

Though death is a constant companion throughout the book, MacNish rejected the idea that alcohol was the cause of ‘spontaneous combustion’ of the human body. He absolutely rejected fanciful American tales of drunkards being ‘blown up in consequence of their breath or eructations catching fire from the application of a lighted candle’ and, though he cited a number of harrowing cases (mostly ‘women in advanced life’) he expressed doubts as to whether this phenomenon truly existed, demanding ‘authenticated facts’ rather than mere ‘hypothesis and loose analogy’.

Spontaneous combustion of the human body was a very frequent subject of newspaper articles in the nineteenth century and MacNish’s scepticism was ahead of his time.

Appropriately, perhaps, he concluded his book by stressing the virtues of water. Though it was acceptable for older men (that’s me) to take ‘moderate allowance to recruit the vigour which approaching age steals from the frame’, this was not so for those less advanced in age and without the necessity of manual labour. For such men, ‘water is the best drink’ since ‘his blood flows as cool and as pure as the element he quaffs; his brain is clear and composed; he is not encumbered with any useless corpulency; his body is free of all bad humours, his stomach of all bad digestions; and his appetite is healthy and natural’.

It is perhaps unfair, then, to note that McNish died tragically young of typhoid, a waterborne disease, in 1837.

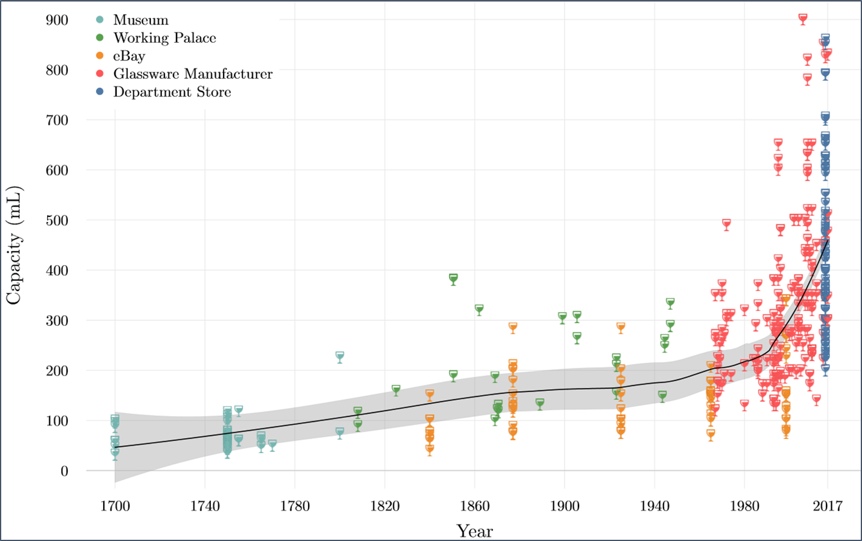

GlassCapacity-MeanTimeTrend – reproduced by kind permission of Dominique-Laurent Couturier, University of Cambridge

GlassCapacity-MeanTimeTrend – reproduced by kind permission of Dominique-Laurent Couturier, University of Cambridge